MachineLearning AI Save

This repository contains all the work that I regularly did and studied from Medium blogs, several research papers, and other Repos (related/unrelated to the research papers).

250 days of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

This is the 250 days Challenge of Machine Learning, Deep Learning, AI, and Optimization (mini-projects and research papers) that I picked up at the start of January 2022. I have used various environments and Google Colab, and certain environments for this work as it required various libraries and datasets to be downloaded. The following are the problems that I tackled:

- Day 1 (01/01/2022): GradCAM Implementation on Dogs v/s Cats using VGG16 pretrained models

| Classification for Cat (GradCAM-based Explainability) | Classification for Dog (GradCAM-based Explainability) |

|---|---|

|

|

- Day 2 (01/02/2022): Multi-task Learning (focussed on Object Localization)

-

Day 3 (01/03/2022): Implementing GradCAM on Computer Vision problems

- GradCAM for Semantic Segmentation

- GradCAM for ObjectDetection

| Computer Vision domains | CAM methods used | Detected Images | CAM-based images |

|---|---|---|---|

| Semantic Segmentation | GradCAM |  |

|

| Object Detection | EigenCAM |  |

|

| Object Detection | AblationCAM |  |

|

-

Day 4 (01/04/2022): Deep Learning using PointNet-based Dataset

- Classification

| 3D Point Clouds | Meshes Used | Sampled Meshes |

|---|---|---|

| Beds |  |

|

| Chair | TBA |  |

- Segmentation

- Day 5 (01/05/2022): Graph Neural Network on YouChoose dataset

- Implementing GNNs on YouChoose-Click dataset

- Implementing GNNs on YouChoose-Buy dataset

| Dataset | Loss Curve | Accuracy Curve |

|---|---|---|

| YouChoose-Click |  |

|

| YouChoose-Buy |  |

|

- Day 6 (01/06/2022): Graph neural Network for Recommnedation Systems

- Day 7 (01/07/2022): Vision Transformers for efficient Image Classification

| SN | Training and Validation Metrices |

|---|---|

| 1 |  |

| 2 |  |

- Day 8 (01/08/2022): Graph Neural Networks for Molecular Machine Learning

Loss Metrices

:-------------------------:

-

Day 9 (01/09/2022): Latent 3D Point Cloud Generation using GANs and Auto Encoders

-

Day 10 (01/10/2022): Deep Learning introduced on Audio Signal

-

Day 11 (01/11/2022): Ant-Colony Optimization

Explore Difference between Ant Colony Optimization and Genetic Algorithms for Travelling Salesman Problem.

| Methods Used | Geo-locaion graph |

|---|---|

| Ant Colony Optimization |  |

| Genetic Algorithm |  |

-

Day 12 (01/12/2022): Particle Swarm Optimization

-

Day 13 (01/13/2022): Cuckoo Search Optimization

-

Day 14 (01/14/2022): Physics-based Optimization algorithms Explored the contents of Physics-based optimization techniques such as:

- Tug-Of-War Optimization (Kaveh, A., & Zolghadr, A. (2016). A novel meta-heuristic algorithm: tug of war optimization. Iran University of Science & Technology, 6(4), 469-492.)

- Nuclear Reaction Optimization (Wei, Z., Huang, C., Wang, X., Han, T., & Li, Y. (2019). Nuclear Reaction Optimization: A novel and powerful physics-based algorithm for global optimization. IEEE Access.)

+ So many equations and loops - take time to run on larger dimension

+ General O (g * n * d)

+ Good convergence curse because the used of gaussian-distribution and levy-flight trajectory

+ Use the variant of Differential Evolution

- Henry Gas Solubility Optimization (Hashim, F. A., Houssein, E. H., Mabrouk, M. S., Al-Atabany, W., & Mirjalili, S. (2019). Henry gas solubility optimization: A novel physics-based algorithm. Future Generation Computer Systems, 101, 646-667.)

+ Too much constants and variables

+ Still have some unclear point in Eq. 9 and Algorithm. 1

+ Can improve this algorithm by opposition-based and levy-flight

+ A wrong logic code in line 91 "j = id % self.n_elements" => to "j = id % self.n_clusters" can make algorithm converge faster. I don't know why?

+ Good results come from CEC 2014

- Day 15 (01/15/2022): Human Activity-based Optimization algorithms Explored the contents of Human Activity-based optimization techniques such as:

- Queuing Search Algorithm (Zhang, J., Xiao, M., Gao, L., & Pan, Q. (2018). Queuing search algorithm: A novel metaheuristic algorithm for solving engineering optimization problems. Applied Mathematical Modelling, 63, 464-490.)

-

Day 16 (01/16/2022): Evolutionary Optimization algorithms Explored the contents of Human Activity-based optimization techniques such as: Genetic Algorithms (Holland, J. H. (1992). Genetic algorithms. Scientific american, 267(1), 66-73) Differential Evolution (Storn, R., & Price, K. (1997). Differential evolution–a simple and efficient heuristic for global optimization over continuous spaces. Journal of global optimization, 11(4), 341-359) Coral Reefs Optimization Algorithm (Salcedo-Sanz, S., Del Ser, J., Landa-Torres, I., Gil-López, S., & Portilla-Figueras, J. A. (2014). The coral reefs optimization algorithm: a novel metaheuristic for efficiently solving optimization problems. The Scientific World Journal, 2014)

-

Day 17 (01/17/2022): Swarm-based Optimization algorithms Explored the contents of Swarm-based optimization techniques such as:

- Particle Swarm Optimization (Eberhart, R., & Kennedy, J. (1995, October). A new optimizer using particle swarm theory. In MHS'95. Proceedings of the Sixth International Symposium on Micro Machine and Human Science (pp. 39-43). IEEE)

- Cat Swarm Optimization (Chu, S. C., Tsai, P. W., & Pan, J. S. (2006, August). Cat swarm optimization. In Pacific Rim international conference on artificial intelligence (pp. 854-858). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg)

- Whale Optimization (Mirjalili, S., & Lewis, A. (2016). The whale optimization algorithm. Advances in engineering software, 95, 51-67)

- Bacterial Foraging Optimization (Passino, K. M. (2002). Biomimicry of bacterial foraging for distributed optimization and control. IEEE control systems magazine, 22(3), 52-67)

- Adaptive Bacterial Foraging Optimization (Yan, X., Zhu, Y., Zhang, H., Chen, H., & Niu, B. (2012). An adaptive bacterial foraging optimization algorithm with lifecycle and social learning. Discrete Dynamics in Nature and Society, 2012)

- Artificial Bee Colony (Karaboga, D., & Basturk, B. (2007, June). Artificial bee colony (ABC) optimization algorithm for solving constrained optimization problems. In International fuzzy systems association world congress (pp. 789-798). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg)

- Pathfinder Algorithm (Yapici, H., & Cetinkaya, N. (2019). A new meta-heuristic optimizer: Pathfinder algorithm. Applied Soft Computing, 78, 545-568)

- Harris Hawks Optimization (Heidari, A. A., Mirjalili, S., Faris, H., Aljarah, I., Mafarja, M., & Chen, H. (2019). Harris hawks optimization: Algorithm and applications. Future Generation Computer Systems, 97, 849-872)

- Sailfish Optimizer (Shadravan, S., Naji, H. R., & Bardsiri, V. K. (2019). The Sailfish Optimizer: A novel nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithm for solving constrained engineering optimization problems. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, 80, 20-34)

Credits (from Day 14--17): Learnt a lot due to Nguyen Van Thieu and his repository that deals with metaheuristic algorithms. Plan to use these algorithms in the problems enountered later onwards.

-

Day 18 (01/18/2022): Grey Wolf Optimization Algorithm

-

Day 19 (01/19/2022): Firefly Optimization Algorithm

-

Day 20 (01/20/2022): Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy Referenced from CMA (can be installed using

pip install cma)

| CMAES without bounds | CMAES with bounds |

|---|---|

|

|

Refered from: Nikolaus Hansen, Dirk Arnold, Anne Auger. Evolution Strategies. Janusz Kacprzyk; Witold Pedrycz. Handbook of Computational Intelligence, Springer, 2015, 978-3-622-43504-5. ffhal-01155533f

- Day 21 (01/21/2022): Copy Move Forgery Detection using SIFT Features

| S. No | Forged Images | Forgery Detection in Images |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

|

| 2 |  |

|

| 3 |  |

|

- Day 22 (01/22/2022): Contour Detection using OpenCV

| Contour Approximation Method | Retrieval Method | Actual Image | Contours Detected |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHAIN_APPROX_NONE | RETR_TREE |  |

|

| CHAIN_APPROX_SIMPLE | RETR_TREE |  |

|

| CHAIN_APPROX_SIMPLE | RETR_CCOMP |  |

|

| CHAIN_APPROX_SIMPLE | RETR_LIST |  |

|

| CHAIN_APPROX_SIMPLE | RETR_EXTERNAL |  |

|

| CHAIN_APPROX_SIMPLE | RETR_TREE |  |

|

Referenced from here

- Day 23 (01/23/2022): Simple Background Detection using OpenCV

| File used | Actual File | Estimated Background |

|---|---|---|

| Video 1 |  |

|

-

Day 24 (01/24/2022): Basics of Quantum Machine Learning with TensorFlow-Quantum Part 1

-

Day 25 (01/25/2022): Basics of Quantum Machine Learning with TensorFlow-Quantum Part 2

-

Day 26 (01/26/2022): Latent Space Representation Part 1: AutoEncoders

| Methods used | t-SNE Representation |

|---|---|

| Using PCA |  |

| Using Autoencoders |  |

- Day 27 (01/27/2022): Latent Space Representation Part 2: Variational AutoEncoders

| Methods used | Representation |

|---|---|

| Using PCA |  |

| Using Variational Autoencoders |  |

- Day 28 (01/28/2022): Latent Space Representation Part 3: Deep Convolutional Generative Adversarial Networks

| Methods used | Representation |

|---|---|

| Using Generative Adversarial Networks |  |

-

Day 29 (01/29/2022): Entity Recognition in Natural Language Processing

-

Day 30 (01/30/2022): Head-Pose Detection using 3D coordinates for Multiple People

| Library Used | Actual Image | Facial Detection | Facial Landmarks | Head Pose Estimation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haar Cascades |  |

|

(To be done) | (To be done) |

| Haar Cascades |  |

|

(To be done) | (To be done) |

| Mult-task Cascaded Convolutional Neural Networks |  |

|

|

|

| Mult-task Cascaded Convolutional Neural Networks |  |

|

|

|

| OpenCV's Deep Neural Network |  |

|

|

|

| OpenCV's Deep Neural Network |  |

|

|

|

(Yet to use Dlib for facial detection.)

- Day 31 (01/31/2022): Depth Estimation for face using OpenCV

| Model Used | Actual Image | Monocular Depth Estimation | Depth Map |

|---|---|---|---|

| MiDaS model for Depth Estimation |  |

|

|

| MiDaS model for Depth Estimation |  |

|

|

Ref: (The model used was Large Model ONNX file)

- Day 32 - 37 (02/01/2022 - 02/06/2022): [Exploring Latent Spaces in Depth]

| Model Used | Paper Link | Pictures |

|---|---|---|

| Auxiliary Classifier GAN | Paper |  |

| Bicycle GAN | Paper |  |

| Conditional GAN | Paper |  |

| Cluster GAN | Paper |  |

| Context Conditional GAN | Paper |  |

| Context Encoder | Paper |  |

| Cycle GAN | Paper |  |

| Deep Convolutional GAN | Paper |  |

| DiscoGANs | Paper |  |

| Enhanced SuperRes GAN | Paper |  |

| InfoGAN | Paper |  |

| MUNIT | Paper |  |

| Pix2Pix | Paper |  |

| PixelDA | Paper | |

| StarGAN | Paper |  |

| SuperRes GAN | Paper |  |

| WGAN DIV | Paper |  |

| WGAN GP | Paper |  |

-

Day 38 (02/07/2022): Human Activity Recognition, Non-Maximum Supression, Object Detection

-

Day 39 (02/08/2022): Pose Estimation using different Algorithms

-

Day 40 (02/09/2022): Optical Flow Estimation

-

Day 41 (02/10/2022): Vision Transformers Explainability

-

Day 42 (02/11/2022): Explainability in Self Driving Cars

-

Day 43 (02/12/2022): TimeSformer Intuition

-

Day 44 (02/13/2022): Image Deraining Implementation using SPANet Referred from: RESCAN by Xia Li et al. The CUDA extension references pyinn by Sergey Zagoruyko and DSC(CF-Caffe) by Xiaowei Hu!!

-

Day 45 (02/14/2022): G-SimCLR Intuition

-

Day 46 (02/15/2022): Topic Modelling in Natural Language Processing

-

Day 47 (02/16/2022): img2pose: Face Alignment and Detection via 6DoF, Face Pose Estimation This repository draws directly from the one mentioned here. I've tried implementing it on different datasets such as the BIWI ad AWFL dataset. Furthermore, the models weren't trained from scratch. The run was meant to be a way to report the numbers in the paper.

Paper accepted to the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 2021

Summary: This repository provides a novel method for six degrees of fredoom (6DoF) detection on multiple faces without the need of prior face detection. After prediction, one can visualize the detections (as show in the figure above), customize projected bounding boxes, or crop and align each face for further processing. See details below.

Paper details

Vítor Albiero, Xingyu Chen, Xi Yin, Guan Pang, Tal Hassner, "img2pose: Face Alignment and Detection via 6DoF, Face Pose Estimation," CVPR, 2021, arXiv:2012.07791

Abstract

We propose real-time, six degrees of freedom (6DoF), 3D face pose estimation without face detection or landmark localization. We observe that estimating the 6DoF rigid transformation of a face is a simpler problem than facial landmark detection, often used for 3D face alignment. In addition, 6DoF offers more information than face bounding box labels. We leverage these observations to make multiple contributions: (a) We describe an easily trained, efficient, Faster R-CNN--based model which regresses 6DoF pose for all faces in the photo, without preliminary face detection. (b) We explain how pose is converted and kept consistent between the input photo and arbitrary crops created while training and evaluating our model. (c) Finally, we show how face poses can replace detection bounding box training labels. Tests on AFLW2000-3D and BIWI show that our method runs at real-time and outperforms state of the art (SotA) face pose estimators. Remarkably, our method also surpasses SotA models of comparable complexity on the WIDER FACE detection benchmark, despite not been optimized on bounding box labels.

Video Spotlight CVPR 2021 Spotlight

Installation

Install dependecies with Python 3.

pip install -r requirements.txt

Install the renderer, which is used to visualize predictions. The renderer implementation is forked from here.

cd Sim3DR

sh build_sim3dr.sh

Training Prepare WIDER FACE dataset First, download our annotations as instructed in Annotations.

Download WIDER FACE dataset and extract to datasets/WIDER_Face.

Then, to create the train and validation files (LMDB), run the following scripts.

python3 convert_json_list_to_lmdb.py \

--json_list ./annotations/WIDER_train_annotations.txt \

--dataset_path ./datasets/WIDER_Face/WIDER_train/images/ \

--dest ./datasets/lmdb/ \

-—train

This first script will generate a LMDB dataset, which contains the training images along with annotations. It will also output a pose mean and std deviation files, which will be used for training and testing.

python3 convert_json_list_to_lmdb.py \

--json_list ./annotations/WIDER_val_annotations.txt \

--dataset_path ./datasets/WIDER_Face/WIDER_val/images/ \

--dest ./datasets/lmdb

This second script will create a LMDB containing the validation images along with annotations.

Train Once the LMDB train/val files are created, to start training simple run the script below.

CUDA_VISIBLE_DEVICES=0 python3 train.py \

--pose_mean ./datasets/lmdb/WIDER_train_annotations_pose_mean.npy \

--pose_stddev ./datasets/lmdb/WIDER_train_annotations_pose_stddev.npy \

--workspace ./workspace/ \

--train_source ./datasets/lmdb/WIDER_train_annotations.lmdb \

--val_source ./datasets/lmdb/WIDER_val_annotations.lmdb \

--prefix trial_1 \

--batch_size 2 \

--lr_plateau \

--early_stop \

--random_flip \

--random_crop \

--max_size 1400

To train with multiple GPUs (in the example below 4 GPUs), use the script below.

python3 -m torch.distributed.launch --nproc_per_node=4 --use_env train.py \

--pose_mean ./datasets/lmdb/WIDER_train_annotations_pose_mean.npy \

--pose_stddev ./datasets/lmdb/WIDER_train_annotations_pose_stddev.npy \

--workspace ./workspace/ \

--train_source ./datasets/lmdb/WIDER_train_annotations.lmdb \

--val_source ./datasets/lmdb/WIDER_val_annotations.lmdb \

--prefix trial_1 \

--batch_size 2 \

--lr_plateau \

--early_stop \

--random_flip \

--random_crop \

--max_size 1400 \

--distributed

Training on your own dataset If your dataset has facial landmarks and bounding boxes already annotated, store them into JSON files following the same format as in the WIDER FACE annotations.

If not, run the script below to annotate your dataset. You will need a detector and import it inside the script.

python3 utils/annotate_dataset.py

--image_list list_of_images.txt

--output_path ./annotations/dataset_name

After the dataset is annotated, create a list pointing to the JSON files there were saved. Then, follow the steps in Prepare WIDER FACE dataset replacing the WIDER annotations with your own dataset annotations. Once the LMDB and pose files are created, follow the steps in Train replacing the WIDER LMDB and pose files with your dataset own files.

Testing To evaluate with the pretrained model, download the model from Model Zoo, and extract it to the main folder. It will create a folder called models, which contains the model weights and the pose mean and std dev that was used for training.

If evaluating with own trained model, change the pose mean and standard deviation to the ones trained with.

Visualizing trained model To visualize a trained model on the WIDER FACE validation set run the notebook visualize_trained_model_predictions.

WIDER FACE dataset evaluation If you haven't done already, download the WIDER FACE dataset and extract to datasets/WIDER_Face.

Download the pre-trained model.

python3 evaluation/evaluate_wider.py \

--dataset_path datasets/WIDER_Face/WIDER_val/images/ \

--dataset_list datasets/WIDER_Face/wider_face_split/wider_face_val_bbx_gt.txt \

--pose_mean models/WIDER_train_pose_mean_v1.npy \

--pose_stddev models/WIDER_train_pose_stddev_v1.npy \

--pretrained_path models/img2pose_v1.pth \

--output_path results/WIDER_FACE/Val/

To check mAP and plot curves, download the eval tools and point to results/WIDER_FACE/Val.

AFLW2000-3D dataset evaluation Download the AFLW2000-3D dataset and unzip to datasets/AFLW2000.

Download the fine-tuned model.

Run the notebook aflw_2000_3d_evaluation.

BIWI dataset evaluation Download the BIWI dataset and unzip to datasets/BIWI.

Download the fine-tuned model.

Run the notebook biwi_evaluation.

Testing on your own images

Run the notebook test_own_images.

Output customization

For every face detected, the model outputs by default:

- Pose: rx, ry, rz, tx, ty, tz

- Projected bounding boxes: left, top, right, bottom

- Face scores: 0 to 1

Since the projected bounding box without expansion ends at the start of the forehead, we provide a way of expanding the forehead invidually, along with default x and y expansion.

To customize the size of the projected bounding boxes, when creating the model change any of the bounding box expansion variables as shown below (a complete example can be seen at visualize_trained_model_predictions).

# how much to expand in width

bbox_x_factor = 1.1

# how much to expand in height

bbox_y_factor = 1.1

# how much to expand in the forehead

expand_forehead = 0.3

img2pose_model = img2poseModel(

...,

bbox_x_factor=bbox_x_factor,

bbox_y_factor=bbox_y_factor,

expand_forehead=expand_forehead,

)

Align faces To detect and align faces, simply run the command below, passing the path to the images you want to detect and align and the path to save them.

python3 run_face_alignment.py \

--pose_mean models/WIDER_train_pose_mean_v1.npy \

--pose_stddev models/WIDER_train_pose_stddev_v1.npy \

--pretrained_path models/img2pose_v1.pth \

--images_path image_path_or_list \

--output_path path_to_save_aligned_faces

Resources

Referred from here directly.

-

Day 48 (02/17/2022): Geometric Deep Learning Tutorials Part I This folder contains the tutorials that I watched and implemented on Day 48th of 100 days of AI. I also referred to some of the papers, medium articles, and distill hub articles to improve my basics of Geometric Deep Learning.

-

Day 49 (02/18/2022): Geometric Deep Learning Tutorials Part II This was the follow-up for the Geometric Deep Learning that I did on Day 48th. Today I read few research papers from ICML for Geometric Deep Learning and Graph Representation Learning.

-

Day 50 (02/19/2022): Topic Modelling using LSI

-

Day 51 (02/20/2022): Semantic Segmentation using Multimodal Learning Intuition

Segmentation of differenct components of a scene using deep learning & Computer Vision. Making uses of multiple modalities of a same scene ( eg: RGB image, Depth Image, NIR etc) gave better results compared to individual modalities.

We used Keras for implementation of Fully convolutional Network (FCN-32s) trained to predict semantically segmented images of forest like images with rgb & nir_color input images. (check out the presentation @ https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1z8-GeTXvSuVbcez8R6HOG1Tw_F3A-WETahQdTV38_uc/edit?usp=sharing)

Note:

Do the following steps after you download the dataset before you proceed and train your models.

- run preprocess/process.sh (renames images)

- run preprocess/text_file_gen.py (generates txt files for train,val,test used in data generator)

- run preprocess/aug_gen.py (generates augmented image files beforehand the training, dynamic augmentation in runtime is slow an often hangs the training process)

The Following list describes the files :

Improved Architecture with Augmentation & Dropout

- late_fusion_improveed.py (late_fusion FCN TRAINING FILE, Augmentation= Yes, Dropout= Yes)

- late_fusion_improved_predict.py (predict with improved architecture)

- late_fusion_improved_saved_model.hdf5 (Architecture & weights of improved model)

Old Architecture without Augmentation & Dropout

- late_fusion_old.py (late_fusion FCN TRAINING FILE, Augmentation= No, Dropout= No)

- late_fusion_old_predict.py() (predict with old architecture)

- late_fusion_improved_saved_model.hdf5 (Architecture & weights of old model)

Architecture:

Architecture Reference (first two models in this link): http://deepscene.cs.uni-freiburg.de/index.html

Architecture Reference (first two models in this link): http://deepscene.cs.uni-freiburg.de/index.html

Dataset:

Dataset Reference (Freiburg forest multimodal/spectral annotated): http://deepscene.cs.uni-freiburg.de/index.html#datasets

Dataset Reference (Freiburg forest multimodal/spectral annotated): http://deepscene.cs.uni-freiburg.de/index.html#datasets

Note:Since the dataset is too small the training will overfit. To overcome this and train a generalized classifier image augmentation is done.

Images are transformed geometrically with a combination of transsformations and added to the dataset before training.

Training: Loss : Categorical Cross Entropy

Optimizer : Stochastic gradient descent with lr = 0.008, momentum = 0.9, decay=1e-6

Results:

NOTE: This following files in the repository ::

1.Deepscene/nir_rgb_segmentation_arc_1.py :: ("CHANNEL-STACKING MODEL") 2.Deepscene/nir_rgb_segmentation_arc_2.py :: ("LATE-FUSION MODEL") 3.Deepscene/nir_rgb_segmentation_arc_3.py :: ("Convoluted Mixture of Deep Experts (CMoDE) Model")

are the exact replicas of the architectures described in Deepscene website.

-

Day 52 (02/21/2022): Visually Indicated Sound-Generation Intuition

-

Day 53 (02/22/2022): Diverse and Specific Image Captioning Intuition

This contains the code for Generating Diverse and Meaningful Captions: Unsupervised Specificity Optimization for Image Captioning (Lindh et al., 2018) to appear in Artificial Neural Networks and Machine Learning - ICANN 2018.

A detailed description of the work, including test results, can be found in our paper: [publisher version] [author version]

Please consider citing if you use the code:

@inproceedings{lindh_generating_2018,

series = {Lecture {Notes} in {Computer} {Science}},

title = {Generating {Diverse} and {Meaningful} {Captions}},

isbn = {978-3-030-01418-6},

doi = {10.1007/978-3-030-01418-6_18},

language = {en},

booktitle = {Artificial {Neural} {Networks} and {Machine} {Learning} – {ICANN} 2018},

publisher = {Springer International Publishing},

author = {Lindh, Annika and Ross, Robert J. and Mahalunkar, Abhijit and Salton, Giancarlo and Kelleher, John D.},

editor = {Kůrková, Věra and Manolopoulos, Yannis and Hammer, Barbara and Iliadis, Lazaros and Maglogiannis, Ilias},

year = {2018},

keywords = {Computer Vision, Contrastive Learning, Deep Learning, Diversity, Image Captioning, Image Retrieval, Machine Learning, MS COCO, Multimodal Training, Natural Language Generation, Natural Language Processing, Neural Networks, Specificity},

pages = {176--187}

}

The code in this repository builds on the code from the following two repositories:

https://github.com/ruotianluo/ImageCaptioning.pytorch

https://github.com/facebookresearch/SentEval/

A note is included at the top of each file that has been changed from its original state. We make these changes (and our own original files) available under Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International where applicable (see LICENSE.txt in the root of this repository).

The code from the two repos listed above retain their original licenses. Please see visit their repositories for further details. The SentEval folder in our repo contains the LICENSE document for SentEval at the time of our fork.

Requirements

Python 2.7 (built with the tk-dev package installed)

PyTorch 0.3.1 and torchvision

h5py 2.7.1

sklearn 0.19.1

scipy 1.0.1

scikit-image (skimage) 0.13.1

ijson

Tensorflow is needed if you want to generate learning curve graphs (recommended!)

Setup for the Image Captioning side

For ImageCaptioning.pytorch (previously known as neuraltalk2.pytorch) you need the pretrained resnet model found here, which should be placed under combined_model/neuraltalk2_pytorch/data/imagenet_weights.

You will also need the cocotalk_label.h5 and cocotalk.json from here and the pretrained Image Captioning model from the topdown directory.

To run the prepro scripts for the Image Captioning model, first download the coco images from link. You should put the train2014/ and val2014/ in the same directory, denoted as $IMAGE_ROOT during preprocessing.

There’s some problems with the official COCO images. See this issue about manually replacing one image in the dataset. You should also run the script under utilities/check_file_types.py that will help you find one or two PNG images that are incorrectly marked as JPG images. I had to manually convert these to JPG files and replace them.

Next, download the preprocessed coco captions from link from Karpathy's homepage. Extract dataset_coco.json from the zip file and copy it in to data/. This file provides preprocessed captions and the train-val-test splits.

Once we have these, we can now invoke the prepro_*.py script, which will read all of this in and create a dataset (two feature folders, a hdf5 label file and a json file):

$ python scripts/prepro_labels.py --input_json data/dataset_coco.json --output_json data/cocotalk.json --output_h5 data/cocotalk

$ python scripts/prepro_feats.py --input_json data/dataset_coco.json --output_dir data/cocotalk --images_root $IMAGE_ROOT

See https://github.com/ruotianluo/ImageCaptioning.pytorch for more info on the scripts if needed.

Setup for the Image Retrieval side

You will need to train a SentEval model according to the instructions here using their pretrained InferSent embedder. IMPORTANT: Because of a change in SentEval, you will need to pull commit c7c7b3a instead of the latest version.

You also need the GloVe embeddings you used for this when you’re training the full combined model.

Setup for the combined model

You will need the official coco-caption evaluation code which you can find here:

https://github.com/tylin/coco-caption

This should go in a folder called coco_caption under src/combined_model/neuraltalk2_pytorch

Run the training

$ cd src/combined_model

$ python SentEval/examples/launch_training.py --id <your_model_id> --checkpoint_path <path_to_save_model> --start_from <directory_pretrained_captioning_model> --learning_rate 0.0000001 --max_epochs 10 --best_model_condition mean_rank --loss_function pairwise_cosine --losses_log_every 10000 --save_checkpoint_every 10000 --batch_size 2 --caption_model topdown --input_json neuraltalk2_pytorch/data/cocotalk.json --input_fc_dir neuraltalk2_pytorch/data/cocotalk_fc --input_att_dir neuraltalk2_pytorch/data/cocotalk_att --input_label_h5 neuraltalk2_pytorch/data/cocotalk_label.h5 --learning_rate_decay_start 0 --senteval_model <your_trained_senteval_model> --language_eval 1 --split val

The --loss_function options used for the models in the paper:

Cos = cosine_similarity

DP = direct_similarity

CCos = pairwise_cosine

CDP = pairwise_similarity

See combined_model/neuraltalk2_pytorch/opts.py for a list of the available parameters.

Run the test

$ cd src/combined_model

$ python SentEval/examples/launch_test.py --id <your_model_id> --checkpoint_path <path_to_model> --start_from <path_to_model> --load_best_model 1 --loss_function pairwise_cosine --batch_size 2 --caption_model topdown --input_json neuraltalk2_pytorch/data/cocotalk.json --input_fc_dir neuraltalk2_pytorch/data/cocotalk_fc --input_att_dir neuraltalk2_pytorch/data/cocotalk_att --input_label_h5 neuraltalk2_pytorch/data/cocotalk_label.h5 --learning_rate_decay_start 0 --senteval_model <your_trained_senteval_model> --language_eval 1 --split test

To test the baseline or the latest version of a model (instead of the one marked with 'best' in the name) use:

--load_best_model 0

The --loss_function option will only decide which internal loss function to report the result for. No extra training will be carried out, and the other results won't be affected by this choice.

-

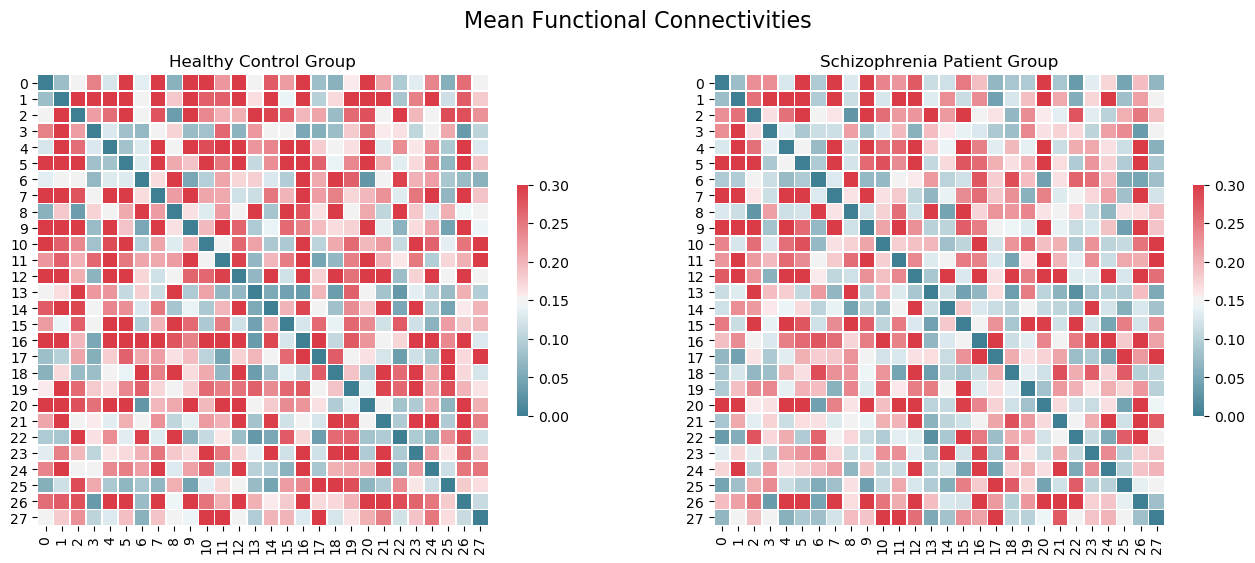

Day 54 (02/23/2022): Brain Activity Classification and Regressive Analysis

-

Day 55 (02/24/2022): Singular Value Decomposition applications in Image Processing

-

Day 56 (02/25/2022): Knowledge Distillation Introduction

knowledge-distillation-pytorch

- Exploring knowledge distillation of DNNs for efficient hardware solutions

- Author Credits: Haitong Li

- Dataset: CIFAR-10

Features

- A framework for exploring "shallow" and "deep" knowledge distillation (KD) experiments

- Hyperparameters defined by "params.json" universally (avoiding long argparser commands)

- Hyperparameter searching and result synthesizing (as a table)

- Progress bar, tensorboard support, and checkpoint saving/loading (utils.py)

- Pretrained teacher models available for download

Install

- Install the dependencies (including Pytorch)

pip install -r requirements.txt

Organizatoin:

- ./train.py: main entrance for train/eval with or without KD on CIFAR-10

- ./experiments/: json files for each experiment; dir for hypersearch

- ./model/: teacher and student DNNs, knowledge distillation (KD) loss defination, dataloader

Key notes about usage for your experiments:

- Download the zip file for pretrained teacher model checkpoints from this Box folder

- Simply move the unzipped subfolders into 'knowledge-distillation-pytorch/experiments/' (replacing the existing ones if necessary; follow the default path naming)

- Call train.py to start training 5-layer CNN with ResNet-18's dark knowledge, or training ResNet-18 with state-of-the-art deeper models distilled

- Use search_hyperparams.py for hypersearch

- Hyperparameters are defined in params.json files universally. Refer to the header of search_hyperparams.py for details

Train (dataset: CIFAR-10)

Note: all the hyperparameters can be found and modified in 'params.json' under 'model_dir'

-- Train a 5-layer CNN with knowledge distilled from a pre-trained ResNet-18 model

python train.py --model_dir experiments/cnn_distill

-- Train a ResNet-18 model with knowledge distilled from a pre-trained ResNext-29 teacher

python train.py --model_dir experiments/resnet18_distill/resnext_teacher

-- Hyperparameter search for a specified experiment ('parent_dir/params.json')

python search_hyperparams.py --parent_dir experiments/cnn_distill_alpha_temp

--Synthesize results of the recent hypersearch experiments

python synthesize_results.py --parent_dir experiments/cnn_distill_alpha_temp

Results: "Shallow" and "Deep" Distillation

Quick takeaways (more details to be added):

- Knowledge distillation provides regularization for both shallow DNNs and state-of-the-art DNNs

- Having unlabeled or partial dataset can benefit from dark knowledge of teacher models

-Knowledge distillation from ResNet-18 to 5-layer CNN

| Model | Dropout = 0.5 | No Dropout |

|---|---|---|

| 5-layer CNN | 83.51% | 84.74% |

| 5-layer CNN w/ ResNet18 | 84.49% | 85.69% |

-Knowledge distillation from deeper models to ResNet-18

| Model | Test Accuracy |

|---|---|

| Baseline ResNet-18 | 94.175% |

| + KD WideResNet-28-10 | 94.333% |

| + KD PreResNet-110 | 94.531% |

| + KD DenseNet-100 | 94.729% |

| + KD ResNext-29-8 | 94.788% |

References

H. Li, "Exploring knowledge distillation of Deep neural nets for efficient hardware solutions," CS230 Report, 2018

Hinton, Geoffrey, Oriol Vinyals, and Jeff Dean. "Distilling the knowledge in a neural network." arXiv preprint arXiv:1503.02531 (2015).

Romero, A., Ballas, N., Kahou, S. E., Chassang, A., Gatta, C., & Bengio, Y. (2014). Fitnets: Hints for thin deep nets. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6550.

https://github.com/cs230-stanford/cs230-stanford.github.io

https://github.com/bearpaw/pytorch-classification

-

Day 57 (02/26/2022): 3D Morphable Face Models Intuition They are using Mobilenet to regress sparse 3D Morphable face models (by default (by using only 40 best shape parameters, 10 best shape base parameters (using PCA), 12 parameters for rotational and translation in the equation)) (that seem like landmarks) and then these are then optimized using 2 cost functions (the WPDC and VDC) through an adaptive k-step lookahead (which is the meta-joint optimization). Here, we can see the differences between different Morphable Face Models.

-

Day 58 (02/27/2022): Federated Learning in Pytorch

Implementation of the vanilla federated learning paper : Communication-Efficient Learning of Deep Networks from Decentralized Data. Reference github respository here.

Experiments are produced on MNIST, Fashion MNIST and CIFAR10 (both IID and non-IID). In case of non-IID, the data amongst the users can be split equally or unequally.

Since the purpose of these experiments are to illustrate the effectiveness of the federated learning paradigm, only simple models such as MLP and CNN are used.

Requirments Install all the packages from requirments.txt

pip install -r requirements.txt

Data

- Download train and test datasets manually or they will be automatically downloaded from torchvision datasets.

- Experiments are run on Mnist, Fashion Mnist and Cifar.

- To use your own dataset: Move your dataset to data directory and write a wrapper on pytorch dataset class.

Results on MNIST Baseline Experiment: The experiment involves training a single model in the conventional way.

Parameters:

-

Optimizer:: SGD -

Learning Rate:0.01

Table 1: Test accuracy after training for 10 epochs:

| Model | Test Acc |

|---|---|

| MLP | 92.71% |

| CNN | 98.42% |

Federated Experiment: The experiment involves training a global model in the federated setting. Federated parameters (default values):

-

Fraction of users (C): 0.1 -

Local Batch size (B): 10 -

Local Epochs (E): 10 -

Optimizer: SGD -

Learning Rate: 0.01

Table 2:Test accuracy after training for 10 global epochs with: | Model | IID | Non-IID (equal)| | ----- | ----- |---- | | MLP | 88.38% | 73.49% | | CNN | 97.28% | 75.94% | Further Readings Find the papers and reading that I had done for understanding this topic more in depth here.

- Day 59 (02/28/2022): Removing Features from Images

- Day 60 (03/01/2022): Slot Filling, Named Entity Recognition, Intent Detection: An Intuition and Review

- Day 61 (03/02/2022): Super Resolution in Remote Sensing I worked at a Remote Sensing company and one of my proposed idea over there was to utilize Deep Learning for saving on the budget. This was because it gets very expensive to purchase High Resolution Imagery from the satellite companies. So, I proposed to utilize Super Resolution based Deep Learning for increasing the Resolution from Low Resolution Imagery. Here, I am going to implement a repository for the same and have the visualization for the same in a Graphical Interchange Format.

- Day 62 (03/03/2022): Deep Dreaming in Computer Vision

- Day 63 (03/04/2022): View Synthesis using Computer Vision

| Novel View Synthesis | Scene Editting + No NVS + GT Depth |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

-

Day 64 (03/05/2022): Deep Reinforcement Learning in Atari Games

RL-Atari-gym

Reinforcement Learning on Atari Games and Control Entrance of program:

- Breakout.py

How to run

(1). Check DDQN_params.json, make sure that every parameter is set right.

GAME_NAME # Set the game's name . This will help you create a new dir to save your result.

MODEL_NAME # Set the algorithms and model you are using. This is only used for rename your result file, so you still need

to change the model isntanace manually.

MAX_ITERATION # In original paper, this is set to 25,000,000. But here we set it to 5,000,000 for Breakout.(2,500,000 for Pong will suffice.)

num_episodes # Max number of episodes. We set it to a huge number in default so normally this stop condition

usually won't be satisfied.

# the program will stop when one of the above condition is met.

(2). Select the model and game environment instance manually. Currently, we are mainly focusing on DQN_CNN_2015 and Dueling_DQN_2016_Modified.

(3). Run and prey :)

NOTE: When the program is running, wait for a couple of minutes and take a look at the estimated time printed in the

console. Stop early and decrease the MAX_ITERATION if you cannot wait for such a long time. (Recommendation: typically,

24h could be a reasonable running time for your first training process. Since you can continue training your model, take

a rest for both you and computer and check the saved figures to see if your model has a promising future. Hope so ~ )

How to continue training the model

The breakout.py will automatically save the mid point state and variables for you if the program exit w/o exception.

-

set the middle_point_json file path.

-

check DDQN_params.json, make sure that every parameter is set right. Typically, you need to set a new

MAX_ITERATIONornum_episodes. -

Run and prey :)

How to evaluate the Model

evaluation.py helps you evaluate the model. First, please modified param_json_fname and model_list_fname to your

directory. Second, change the game environment instance and the model instance. Then run.

Results Structure

The program will automatically create the the directory like this:

├── GIF_Reuslts

│ └── ModelName:2015_CNN_DQN-GameName:Breakout-Time:03-28-2020-18-20-28

│ ├── Iterations:100000-Reward:0.69-Time:03-28-2020-18-20-27-EvalReward:0.0.gif

│ ├── Iterations:200000-Reward:0.69-Time:03-28-2020-18-20-27-EvalReward:1.0.gif

├── Results

│ ├── ModelName:2015_CNN_DQN-GameName:Breakout-Time:03-28-2020-18-20-28-Eval.pkl

│ └── ModelName:2015_CNN_DQN-GameName:Breakout-Time:03-28-2020-18-20-28.pkl

├── DDQN_params.json

Please zip these three files/folders and upload it to our shared google drive. Rename it, e.g. ModelName:2015_CNN_DQN-GameName:Breakout-Time:03-28-2020-18-20-28.

PS:

GIF_Reuslts record the game process

Results contains the history of training and eval process, which can be used to visualize later.

DDQN_params.json contains your algorithm settings, which should match your Results and GIF_Reuslts.

-

Day 65 (03/06/2022): Molecular Chemistry using Machine Learning

-

Day 66 (03/07/2022): Face Frontalization

Pytorch implementation of a face frontalization GAN

Introduction

Screenwriters never cease to amuse us with bizarre portrayals of the tech industry, ranging from cringeworthy to hilarious. With the current advances in artificial intelligence, however, some of the most unrealistic technologies from the TV screens are coming to life. For example, the Enhance software from CSI: NY (or Les Experts : Manhattan for the francophone readers) has already been outshone by the state-of-the-art Super Resolution neural networks. On a more extreme side of the imagination, there is Enemy of the state:

"Rotating [a video surveillance footage] 75 degrees around the vertical" must have seemed completely nonsensical long after 1998 when the movie came out, evinced by the youtube comments below this particular excerpt:

Despite the apparent pessimism of the audience, thanks to machine learning today anyone with a little bit of Python knowledge and a large enough dataset can take a stab at writing a sci-fi drama worthy program.

The face frontalization problem

Forget MNIST, forget the boring cat vs. dog classifiers, today we are going to learn how to do something far more exciting! This project was inspired by the impressive work by R. Huang et al. (Beyond Face Rotation: Global and Local Perception GAN for Photorealistic and Identity Preserving Frontal View Synthesis), in which the authors synthesise frontal views of people's faces given their images at various angles. Below is Figure 3 from that paper, in which they compare their results [1] to previous work [2-6]:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input | [1] | [2] | [3] | [4] | [5] | [6] | Actual frontal | |||||||

| Comparison of multiple face frontalization methods [1] | ||||||||||||||

We are not going to try to reproduce the state-of-the-art model by R. Huang et al. Instead, we will construct and train a face frontalization model, producing reasonable results in a single afternoon:

| input |  |

|---|---|

| generated output |  |

Additionally, we will go over:

-

How to use NVIDIA's

DALIlibrary for highly optimized pre-processing of images on the GPU and feeding them into a deep learning model. -

How to code a Generative Adversarial Network, praised as “the most interesting idea in the last ten years in Machine Learning” by Yann LeCun, the director of Facebook AI, in

PyTorch

You will also have your very own Generative Adversarial Network set up to be trained on a dataset of your choice. Without further ado, let's dig in!

Setting Up Your Data

At the heart of any machine learning project, lies the data. Unfortunately, Scaleway cannot provide the CMU Multi-PIE Face Database that we used for training due to copyright, so we shall proceed assuming you already have a dataset that you would like to train your model on. In order to make use of NVIDIA Data Loading Library (DALI), the images should be in JPEG format. The dimensions of the images do not matter, since we have DALI to resize all the inputs to the input size required by our network (128 x 128 pixels), but a 1:1 ratio is desirable to obtain the most realistic synthesised images. The advantage of using DALI over, e.g., a standard PyTorch Dataset, is that whatever pre-processing (resizing, cropping, etc) is necessary, is performed on the GPU rather than the CPU, after which pre-processed images on the GPU are fed straight into the neural network.

Managing our dataset:

For the face frontalization project, we set up our dataset in the following way: the dataset folder contains a subfolder and a target frontal image for each person (aka subject). In principle, the names of the subfolders and the target images do not have to be identical (as they are in the Figure below), but if we are to separately sort all the subfolders and all the targets alphanumerically, the ones corresponding to the same subject must appear at the same position on the two lists of names.

As you can see, subfolder 001/ corresponding to subject 001 contains images of the person pictured in 001.jpg - these are closely cropped images of the face under different poses, lighting conditions, and varying face expressions. For the purposes of face frontalization, it is crucial to have the frontal images aligned as close to one another as possible, whereas the other (profile) images have a little bit more leeway.

For instance, our target frontal images are all squares and cropped in such a way that the bottom of the person's chin is located at the bottom of the image, and the centred point between the inner corners of the eyes is situated at 0.8h above and 0.5h to the right of the lower left corner (h being the image's height). This way, once the images are resized to 128 x 128, the face features all appear at more or less the same locations on the images in the training set, and the network can learn to generate the said features and combine them together into realistic synthetic faces.

Building a DALI Pipeline:

We are now going to build a pipeline for our dataset that is going to inherit from nvidia.dali.pipeline.Pipeline. At the time of writing, DALI does not directly support reading (image, image) pairs from a directory, so we will be making use of nvidia.dali.ops.ExternalSource() to pass the inputs and the targets to the pipeline.

data.py

import collections

from random import shuffle

import os

from os import listdir

from os.path import join

import numpy as np

from nvidia.dali.pipeline import Pipeline

import nvidia.dali.ops as ops

import nvidia.dali.types as types

def is_jpeg(filename):

return any(filename.endswith(extension) for extension in [".jpg", ".jpeg"])

def get_subdirs(directory):

subdirs = sorted([join(directory,name) for name in sorted(os.listdir(directory)) if os.path.isdir(os.path.join(directory, name))])

return subdirs

flatten = lambda l: [item for sublist in l for item in sublist]

class ExternalInputIterator(object):

def __init__(self, imageset_dir, batch_size, random_shuffle=False):

self.images_dir = imageset_dir

self.batch_size = batch_size

# First, figure out what are the inputs and what are the targets in your directory structure:

# Get a list of filenames for the target (frontal) images

self.frontals = np.array([join(imageset_dir, frontal_file) for frontal_file in sorted(os.listdir(imageset_dir)) if is_jpeg(frontal_file)])

# Get a list of lists of filenames for the input (profile) images for each person

profile_files = [[join(person_dir, profile_file) for profile_file in sorted(os.listdir(person_dir)) if is_jpeg(profile_file)] for person_dir in get_subdirs(imageset_dir)]

# Build a flat list of frontal indices, corresponding to the *flattened* profile_files

# The reason we are doing it this way is that we need to keep track of the multiple inputs corresponding to each target

frontal_ind = []

for ind, profiles in enumerate(profile_files):

frontal_ind += [ind]*len(profiles)

self.frontal_indices = np.array(frontal_ind)

# Now that we have built frontal_indices, we can flatten profile_files

self.profiles = np.array(flatten(profile_files))

# Shuffle the (input, target) pairs if necessary: in practice, it is profiles and frontal_indices that get shuffled

if random_shuffle:

ind = np.array(range(len(self.frontal_indices)))

shuffle(ind)

self.profiles = self.profiles[ind]

self.frontal_indices = self.frontal_indices[ind]

def __iter__(self):

self.i = 0

self.n = len(self.frontal_indices)

return self

# Return a batch of (input, target) pairs

def __next__(self):

profiles = []

frontals = []

for _ in range(self.batch_size):

profile_filename = self.profiles[self.i]

frontal_filename = self.frontals[self.frontal_indices[self.i]]

profile = open(profile_filename, 'rb')

frontal = open(frontal_filename, 'rb')

profiles.append(np.frombuffer(profile.read(), dtype = np.uint8))

frontals.append(np.frombuffer(frontal.read(), dtype = np.uint8))

profile.close()

frontal.close()

self.i = (self.i + 1) % self.n

return (profiles, frontals)

next = __next__

class ImagePipeline(Pipeline):

'''

Constructor arguments:

- imageset_dir: directory containing the dataset

- image_size = 128: length of the square that the images will be resized to

- random_shuffle = False

- batch_size = 64

- num_threads = 2

- device_id = 0

'''

def __init__(self, imageset_dir, image_size=128, random_shuffle=False, batch_size=64, num_threads=2, device_id=0):

super(ImagePipeline, self).__init__(batch_size, num_threads, device_id, seed=12)

eii = ExternalInputIterator(imageset_dir, batch_size, random_shuffle)

self.iterator = iter(eii)

self.num_inputs = len(eii.frontal_indices)

# The source for the inputs and targets

self.input = ops.ExternalSource()

self.target = ops.ExternalSource()

# nvJPEGDecoder below accepts CPU inputs, but returns GPU outputs (hence device = "mixed")

self.decode = ops.nvJPEGDecoder(device = "mixed", output_type = types.RGB)

# The rest of pre-processing is done on the GPU

self.res = ops.Resize(device="gpu", resize_x=image_size, resize_y=image_size)

self.norm = ops.NormalizePermute(device="gpu", output_dtype=types.FLOAT,

mean=[128., 128., 128.], std=[128., 128., 128.],

height=image_size, width=image_size)

# epoch_size = number of (profile, frontal) image pairs in the dataset

def epoch_size(self, name = None):

return self.num_inputs

# Define the flow of the data loading and pre-processing

def define_graph(self):

self.profiles = self.input(name="inputs")

self.frontals = self.target(name="targets")

profile_images = self.decode(self.profiles)

profile_images = self.res(profile_images)

profile_output = self.norm(profile_images)

frontal_images = self.decode(self.frontals)

frontal_images = self.res(frontal_images)

frontal_output = self.norm(frontal_images)

return (profile_output, frontal_output)

def iter_setup(self):

(images, targets) = self.iterator.next()

self.feed_input(self.profiles, images)

self.feed_input(self.frontals, targets)

You can now use the ImagePipeline class that you wrote above to load images from your dataset directory, one batch at a time.

If you are using the code from this tutorial inside a Jupyter notebook, here is how you can use an ImagePipeline to display the images:

from __future__ import division

import matplotlib.gridspec as gridspec

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

%matplotlib inline

def show_images(image_batch, batch_size):

columns = 4

rows = (batch_size + 1) // (columns)

fig = plt.figure(figsize = (32,(32 // columns) * rows))

gs = gridspec.GridSpec(rows, columns)

for j in range(rows*columns):

plt.subplot(gs[j])

plt.axis("off")

plt.imshow(np.transpose(image_batch.at(j), (1,2,0)))

batch_size = 8

pipe = ImagePipeline('my_dataset_directory', image_size=128, batch_size=batch_size)

pipe.build()

profiles, frontals = pipe.run()

**The images returned by ImagePipeline are currently on the GPU**

**We need to copy them to the CPU via the asCPU() method in order to display them**

show_images(profiles.asCPU(), batch_size=batch_size)

show_images(frontals.asCPU(), batch_size=batch_size)

Setting Up Your Neural Network

Here comes the fun part, building the network's architecture! We assume that you are already somewhat familiar with the idea behind convolutional neural networks, the architecture of choice for many computer vision applications today. Beyond that, there are two main concepts that we will need for the face Frontalization project, that we shall touch upon in this section:

- the Encoder / Decoder Network(s) and

- the Generative Adversarial Network.

Encoders and Decoders

The Encoder

As mentioned above, our network takes images that are sized 128 by 128 as input. Since the images are in colour (meaning 3 colour channels for each pixel), this results in the input being 3x128x128=49152 dimensional. Perhaps we do not need all 49152 values to describe a person's face? This turns out to be correct: we can get away with a mere 512 dimensional vector (which is simply another way of saying "512 numbers") to encode all the information that we care about. This is an example of dimensionality reduction: the Encoder network (paired with the network responsible for the inverse process, decoding) learns a lower dimensional representation of the input. The architecture of the Encoder may look something like this:

Here we start with input that is 128x128 and has 3 channels. As we pass it through convolutional layers, the size of the input gets smaller and smaller (from 128x128 to 64x64 to 16x16 etc on the Figure above) whereas the number of channels grows (from 3 to 8 to 16 and so on). This reflects the fact that the deeper the convolutional layer, the more abstract are the features that it learns. In the end we get to a layer whose output is sized 1x1, yet has a very high number of channels: 256 in the example depicted above (or 512 in our own network). 256x1 and 1x256 are really the same thing, if you think about it, so another way to put it is that the output of the Encoder is 256 dimensional (with a single channel), so we have reduced the dimensionality of the original input from 49152 to 256! Why would we want to do that? Having this lower dimensional representation helps us prevent overfitting our final model to the training set.

In the end, what we want is a representation (and hence, a model) that is precise enough to fit the training data well, yet does not overfit - meaning, that it can be generalised to the data it has not seen before as well.

The Decoder

As the name suggests, the Decoder's job is the inverse of that of the Encoder. In other words, it takes the low-dimensional representation output of the Encoder and has it go through deconvolutional layers (also known as the transposed convolutional layers). The architecture of the Decoder network is often symmetric to that of the Encoder, although this does not have to be the case. The Encoder and the Decoder are often combined into a single network, whose inputs and outputs are both images:

In our project this Encoder/Decoder network is called the Generator. The Generator takes in a profile image, and (if we do our job right) outputs a frontal one:

It is now time to write it using PyTorch. A two dimensional convolutional layer can be created via torch.nn.Conv2d(in_channels, out_channels, kernel_size, stride, padding). You can now read off the architecture of our Generator network from the code snippet below:

network.py

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import torch.nn.parallel

import torch.optim as optim

from torch.autograd import Variable

def weights_init(m):

classname = m.__class__.__name__

if classname.find('Conv') != -1:

m.weight.data.normal_(0.0, 0.02)

elif classname.find('BatchNorm') != -1:

m.weight.data.normal_(1.0, 0.02)

m.bias.data.fill_(0)

''' Generator network for 128x128 RGB images '''

class G(nn.Module):

def __init__(self):

super(G, self).__init__()

self.main = nn.Sequential(

# Input HxW = 128x128

nn.Conv2d(3, 16, 4, 2, 1), # Output HxW = 64x64

nn.BatchNorm2d(16),

nn.ReLU(True),

nn.Conv2d(16, 32, 4, 2, 1), # Output HxW = 32x32

nn.BatchNorm2d(32),

nn.ReLU(True),

nn.Conv2d(32, 64, 4, 2, 1), # Output HxW = 16x16

nn.BatchNorm2d(64),

nn.ReLU(True),

nn.Conv2d(64, 128, 4, 2, 1), # Output HxW = 8x8

nn.BatchNorm2d(128),

nn.ReLU(True),

nn.Conv2d(128, 256, 4, 2, 1), # Output HxW = 4x4

nn.BatchNorm2d(256),

nn.ReLU(True),

nn.Conv2d(256, 512, 4, 2, 1), # Output HxW = 2x2

nn.MaxPool2d((2,2)),

# At this point, we arrive at our low D representation vector, which is 512 dimensional.

nn.ConvTranspose2d(512, 256, 4, 1, 0, bias = False), # Output HxW = 4x4

nn.BatchNorm2d(256),

nn.ReLU(True),

nn.ConvTranspose2d(256, 128, 4, 2, 1, bias = False), # Output HxW = 8x8

nn.BatchNorm2d(128),

nn.ReLU(True),

nn.ConvTranspose2d(128, 64, 4, 2, 1, bias = False), # Output HxW = 16x16

nn.BatchNorm2d(64),

nn.ReLU(True),

nn.ConvTranspose2d(64, 32, 4, 2, 1, bias = False), # Output HxW = 32x32

nn.BatchNorm2d(32),

nn.ReLU(True),

nn.ConvTranspose2d(32, 16, 4, 2, 1, bias = False), # Output HxW = 64x64

nn.BatchNorm2d(16),

nn.ReLU(True),

nn.ConvTranspose2d(16, 3, 4, 2, 1, bias = False), # Output HxW = 128x128

nn.Tanh()

)

def forward(self, input):

output = self.main(input)

return output

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) are a very exciting deep learning development, which was introduced in a 2014 paper by Ian Goodfellow and collaborators. Without getting into too much detail, here is the idea behind GANs: there are two networks, a generator (perhaps our name choice for the Encoder/Decoder net above makes more sense now) and a discriminator. The Generator's job is to generate synthetic images, but what is the Discriminator to do? The Discriminator is supposed to tell the difference between the real images and the fake ones that were synthesised by the Generator.

Usually, GAN training is carried out in an unsupervised manner. There is an unlabelled dataset of, say, images in a specific domain. The generator will generate some image given random noise as input. The discriminator is then trained to recognise the images from the dataset as real and the output of the generator as fake. As far as the discriminator is concerned, the two categories comprise a labelled dataset. If this sounds like a binary classification problem to you, you won't be surprised to hear that the loss function is the binary cross entropy. The task of the generator is to fool the discriminator. Here is how that is done: first, the generator gives its output to the discriminator. Naturally, that output depends on what the generator's trainable parameters are. The discriminator is not being trained at this point, rather it is used for inference. Instead, it is the generator's weights that are updated in a way that gets the discriminator to accept (as in, label as "real") the synthesised outputs. The updating of the generator's and the discriminator's weights is done alternatively - once each for every batch, as you will see later when we discuss training our model.

Since we are not trying to simply generate faces, the architecture of our Generator is a little different from the one described above (for one thing, it takes real images as inputs, not some random noise, and tries to incorporate certain features of those inputs in its outputs). Our loss function won't be just the cross-entropy either: we have to add an additional component that compares the generator's outputs to the target ones. This could be, for instance, a pixelwise mean square error, or a mean absolute error. These matters are going to be addressed in the Training section of this tutorial.

Before we move on, let us complete the network.py file by providing the code for the Discriminator:

network.py [continued]

''' Discriminator network for 128x128 RGB images '''

class D(nn.Module):

def __init__(self):

super(D, self).__init__()

self.main = nn.Sequential(

nn.Conv2d(3, 16, 4, 2, 1),

nn.LeakyReLU(0.2, inplace = True),

nn.Conv2d(16, 32, 4, 2, 1),

nn.BatchNorm2d(32),

nn.LeakyReLU(0.2, inplace = True),

nn.Conv2d(32, 64, 4, 2, 1),

nn.BatchNorm2d(64),

nn.LeakyReLU(0.2, inplace = True),

nn.Conv2d(64, 128, 4, 2, 1),

nn.BatchNorm2d(128),

nn.LeakyReLU(0.2, inplace = True),

nn.Conv2d(128, 256, 4, 2, 1),

nn.BatchNorm2d(256),

nn.LeakyReLU(0.2, inplace = True),

nn.Conv2d(256, 512, 4, 2, 1),

nn.BatchNorm2d(512),

nn.LeakyReLU(0.2, inplace = True),

nn.Conv2d(512, 1, 4, 2, 1, bias = False),

nn.Sigmoid()

)

def forward(self, input):

output = self.main(input)

return output.view(-1)

As you can see, the architecture of the Discriminator is rather similar to that of the Generator, except that it seems to contain only the Encoder part of the latter. Indeed, the goal of the Discriminator is not to output an image, so there is no need for something like a Decoder. Instead, the Discriminator contains layers that process an input image (much like an Encoder would), with the goal of distinguishing real images from the synthetic ones.

From DALI to PyTorch

DALI is a wonderful tool that not only pre-processes images on the fly, but also provides plugins for several popular machine learning frameworks, including PyTorch.

If you used PyTorch before, you may be familiar with its torch.utils.data.Dataset and torch.utils.data.DataLoader classes meant to ease the pre-processing and loading of the data. When using DALI, we combine the aforementioned nvidia.dali.pipeline.Pipeline with nvidia.dali.plugin.pytorch.DALIGenericIterator in order to accomplish the task.

At this point, we are starting to get into the third, and last, Python file that is a part of the face frontalization project. First, let us get the imports out of the way. We'll also set the seeds for the randomised parts of our model in order to have better control over reproducibility of the results:

main.py

from __future__ import print_function

import time

import math

import random

import os

from os import listdir

from os.path import join

from PIL import Image

import numpy as np

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import torch.nn.parallel

import torch.optim as optim

import torchvision.utils as vutils

from torch.autograd import Variable

from nvidia.dali.plugin.pytorch import DALIGenericIterator

from data import ImagePipeline

import network

np.random.seed(42)

random.seed(10)

torch.backends.cudnn.deterministic = True

torch.backends.cudnn.benchmark = False

torch.manual_seed(999)

# Where is your training dataset at?

datapath = 'training_set'

# You can also choose which GPU you want your model to be trained on below:

gpu_id = 0

device = torch.device("cuda", gpu_id)

In order to integrate the ImagePipeline class from data.py into your PyTorch model, you will need to make use of DALIGenericIterator. Constructing one is very straightforward: you only need to pass it a pipeline object, a list of labels for what your pipeline spits out, and the epoch_size of the pipeline. Here is what that looks like:

main.py [continued]

train_pipe = ImagePipeline(datapath, image_size=128, random_shuffle=True, batch_size=30, device_id=gpu_id)

train_pipe.build()

m_train = train_pipe.epoch_size()

print("Size of the training set: ", m_train)

train_pipe_loader = DALIGenericIterator(train_pipe, ["profiles", "frontals"], m_train)

Now you are ready to train.

Training The Model

First, lets get ourselves some neural networks:

main.py [continued]

# Generator:

netG = network.G().to(device)

netG.apply(network.weights_init)

# Discriminator:

netD = network.D().to(device)

netD.apply(network.weights_init)

The Loss Function

Mathematically, training a neural network refers to updating its weights in a way that minimises the loss function. There are multiple choices to be made here, the most crucial, perhaps, being the form of the loss function. We have already touched upon it in our discussion of GANs in Step 3, so we know that we need the binary cross entropy loss for the discriminator, whose job is to classify the images as either real or fake.

However, we also want a pixelwise loss function that will get the generated outputs to not only look like frontal images of people in general, but the right people - same ones that we see in the input profile images. The common ones to use are the so-called L1 loss and L2 loss: you might know them under the names of Mean Absolute Error and Mean Squared Error respectively. In the code below, we'll give you both (in addition to the cross entropy), together with a way to vary the relative importance you place on each of the three.

main.py [continued]

# Here is where you set how important each component of the loss function is:

L1_factor = 0

L2_factor = 1

GAN_factor = 0.0005

criterion = nn.BCELoss() # Binary cross entropy loss

# Optimizers for the generator and the discriminator (Adam is a fancier version of gradient descent with a few more bells and whistles that is used very often):

optimizerD = optim.Adam(netD.parameters(), lr = 0.0002, betas = (0.5, 0.999))

optimizerG = optim.Adam(netG.parameters(), lr = 0.0002, betas = (0.5, 0.999), eps = 1e-8)

# Create a directory for the output files

try:

os.mkdir('output')

except OSError:

pass

start_time = time.time()

# Let's train for 30 epochs (meaning, we go through the entire training set 30 times):

for epoch in range(30):

# Lets keep track of the loss values for each epoch:

loss_L1 = 0

loss_L2 = 0

loss_gan = 0

# Your train_pipe_loader will load the images one batch at a time

# The inner loop iterates over those batches:

for i, data in enumerate(train_pipe_loader, 0):

# These are your images from the current batch:

profile = data[0]['profiles']

frontal = data[0]['frontals']

# TRAINING THE DISCRIMINATOR

netD.zero_grad()

real = Variable(frontal).type('torch.FloatTensor').to(device)

target = Variable(torch.ones(real.size()[0])).to(device)

output = netD(real)

# D should accept the GT images

errD_real = criterion(output, target)

profile = Variable(profile).type('torch.FloatTensor').to(device)

generated = netG(profile)

target = Variable(torch.zeros(real.size()[0])).to(device)

output = netD(generated.detach()) # detach() because we are not training G here

# D should reject the synthetic images

errD_fake = criterion(output, target)

errD = errD_real + errD_fake

errD.backward()

# Update D

optimizerD.step()

# TRAINING THE GENERATOR

netG.zero_grad()

target = Variable(torch.ones(real.size()[0])).to(device)

output = netD(generated)

# G wants to :

# (a) have the synthetic images be accepted by D (= look like frontal images of people)

errG_GAN = criterion(output, target)

# (b) have the synthetic images resemble the ground truth frontal image

errG_L1 = torch.mean(torch.abs(real - generated))

errG_L2 = torch.mean(torch.pow((real - generated), 2))

errG = GAN_factor * errG_GAN + L1_factor * errG_L1 + L2_factor * errG_L2

loss_L1 += errG_L1.item()

loss_L2 += errG_L2.item()

loss_gan += errG_GAN.item()

errG.backward()

# Update G

optimizerG.step()

if epoch == 0:

print('First training epoch completed in ',(time.time() - start_time),' seconds')

# reset the DALI iterator

train_pipe_loader.reset()

# Print the absolute values of three losses to screen:

print('[%d/30] Training absolute losses: L1 %.7f ; L2 %.7f BCE %.7f' % ((epoch + 1), loss_L1/m_train, loss_L2/m_train, loss_gan/m_train,))

# Save the inputs, outputs, and ground truth frontals to files:

vutils.save_image(profile.data, 'output/%03d_input.jpg' % epoch, normalize=True)

vutils.save_image(real.data, 'output/%03d_real.jpg' % epoch, normalize=True)

vutils.save_image(generated.data, 'output/%03d_generated.jpg' % epoch, normalize=True)

# Save the pre-trained Generator as well

torch.save(netG,'output/netG_%d.pt' % epoch)

Training GANs is notoriously difficult, but let us focus on the L2 loss, equal to the sum of squared differences between each pixel of the output and target images. Its value decreases with every epoch, and if we compare the generated images to the real ones of frontal faces, we see that our model is indeed learning to fit the training data:

In the figure above, the upper row are some of the inputs fed into our model during the 22nd training epoch, below are the frontal images generated by our GAN, and at the bottom is the row of the corresponding ground truth images.

Next, lets see how the model performs on data that it has never seen before.

Testing The Model

We are going to test the model we trained in the previous section on the three subjects that appear in the comparison table in the paper Beyond Face Rotation: Global and Local Perception GAN for Photorealistic and Identity Preserving Frontal View Synthesis. These subjects do not appear in our training set; instead, we put the corresponding images in a directory called test_set that has the same structure as the training_set above. The test.py code is going to load a pre-trained generator network that we saved during training, and put the input test images through it, generating the outputs:

test.py

import torch

import torchvision.utils as vutils

from torch.autograd import Variable

from nvidia.dali.plugin.pytorch import DALIGenericIterator

from data import ImagePipeline

device = 'cuda'

datapath = 'test_set'

# Generate frontal images from the test set

def frontalize(model, datapath, mtest):

test_pipe = ImagePipeline(datapath, image_size=128, random_shuffle=False, batch_size=mtest)

test_pipe.build()

test_pipe_loader = DALIGenericIterator(test_pipe, ["profiles", "frontals"], mtest)

with torch.no_grad():

for data in test_pipe_loader:

profile = data[0]['profiles']

frontal = data[0]['frontals']

generated = model(Variable(profile.type('torch.FloatTensor').to(device)))

vutils.save_image(torch.cat((profile, generated.data, frontal)), 'output/test.jpg', nrow=mtest, padding=2, normalize=True)

return

# Load a pre-trained Pytorch model

saved_model = torch.load("https://github.com/AnshMittal1811/MachineLearning-AI/tree/master/066_Face_Frontalization/01_/output/netG_15.pt")

frontalize(saved_model, datapath, 3)

Here are the results of the model above that has been trained for 15 epochs:

Again, here we see input images on top, followed by generated images in the middle and the ground truth ones at the bottom. Naturally, the agreement between the latter two is not as close as that for the images in the training set, yet we see that the network did in fact learn to pick up various facial features such as glasses, thickness of the eyebrows, eye and nose shape etc. In the end, one has to experiment with the hyperparameters of the model to see what works best. We managed to produce the following results in just five training epochs (which take about an hour and a half on the Scaleway RENDER-S GPU instances):

| input |  |

|---|---|

| generated output |  |

Here we have trained the GAN model with parameters as in the code above for the first three epochs, then set the GAN_factor to zero and continued to train only the generator, optimizing the L1 and L2 losses, for two more epochs.

Why use GANs for supervised ML problems?

Generative Adversarial Networks were initially meant for unsupervised machine learning: a typical training set consists of the so-called "real" examples of some data (which are not labeled, unlike in supervised learning), and the goal is to train the network to generate more examples of the same sort of data. However, GANs are increasingly being used for tasks where training inputs have corresponding outputs (i.e., supervised machine learning). Examples include face frontalization, super resolution, etc. What is the benefit of introducing a GAN architecture into such problems?

Let us compare the results of training the Generator network above in a supervised way using only the L2 pixelwise loss, with the combined Generator/Discriminator architecture. In the latter case, the Discriminator is trained to accept the real images, reject the synethic ones, and the Generator learns to fool the Discriminator in addition to optimizing its own L2 loss.

In the first case, the generated images start to resemble human faces early on during training, but the fine features remain blurry for not only for the test set, but also for the training samples for a relatively long time:

Images generated after 20 000 mini batch evaluations (inputs from the training set):

Images generated after 40 000 mini batch evaluations (inputs from the training set):

Mathematically, this can be attributed to the small contribution of these fine features (eyelids, shadows around the mouth, etc) to pixelwise loss. Since longer training times are required to achieve desired accuracy for the training set, this makes such models prone to over-fitting. Introducing GAN into the picture changes things considerably:

Images generated after 20 000 mini batch evaluations (inputs from the training set):

Images generated after 40 000 mini batch evaluations (inputs from the training set):

While our training set does not have enough unique GT frontal images to train an unsupervised GAN with the likes of NVIDIA's Style GAN, the GAN architecture turns out to be very good at generating the above-mentioned fine features, even though it introduces unwanted noise elsewhere. Evidently, these are the details that the discriminator uses to distinguish the real images from the fake ones, facilitating the generation of photorealistic and super-resolved synethic outputs.

For your reference, below are the profile inputs and the ground truth frontals for the images generated above:

An extended version of this article was first published on the Scaleway blog

-

Day 67 (03/08/2022): ECCV2020 Papers and Implementations

-

Day 68 (03/09/2022): Textured 3D generative Adversarial Networks

-

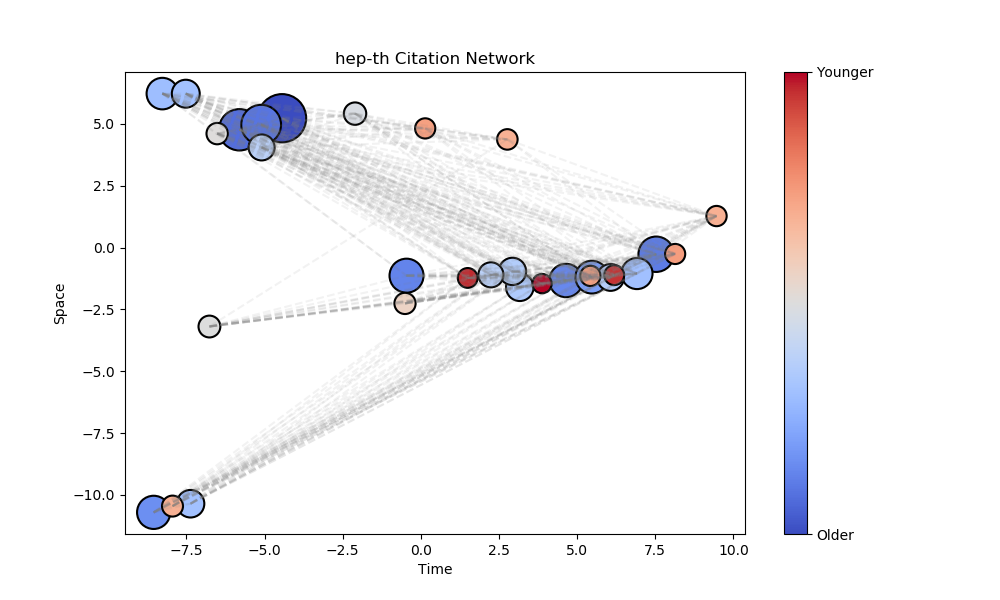

Day 69 (03/10/2022): Hyperbolic Learning

Referred from: Drew Wilimitis

It has been recently established that many real-world networks have a latent geometric structure that resembles negatively curved hyperbolic spaces. Therefore, complex networks, and particularly the hierarchical relationships often found within, can often be more accurately represented by embedding graphs in hyperbolic geometry, rather than flat Euclidean space.

The goal of this project is to provide Python implementations for a few recently published algorithms that leverage hyperbolic geometry for machine learning and network analysis. Several examples are given with real-world datasets, however; the time complexity is far from optimized and this repository is primarily for research purposes - specifically investigating how to integrate downstream supervised learning methods with hyperbolic embeddings.

Contents

Models

-

Poincaré Embeddings:

- Mostly an exploration of the hyperbolic embedding approach used in [1].

- Available implementation in the

gensimlibrary and a PyTorch version released by the authors here.

-

Hyperbolic Multidimensional Scaling: nbviewer

- Finds embedding in Poincaré disk with hyperbolic distances that preserve input dissimilarities [2].

-

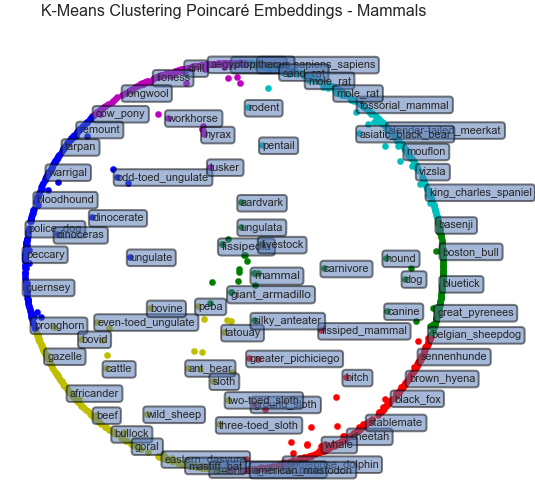

K-Means Clustering in the Hyperboloid Model: nbviewer

- Optimization approach using Frechet means to define a centroid/center of mass in hyperbolic space [3, 4].

-

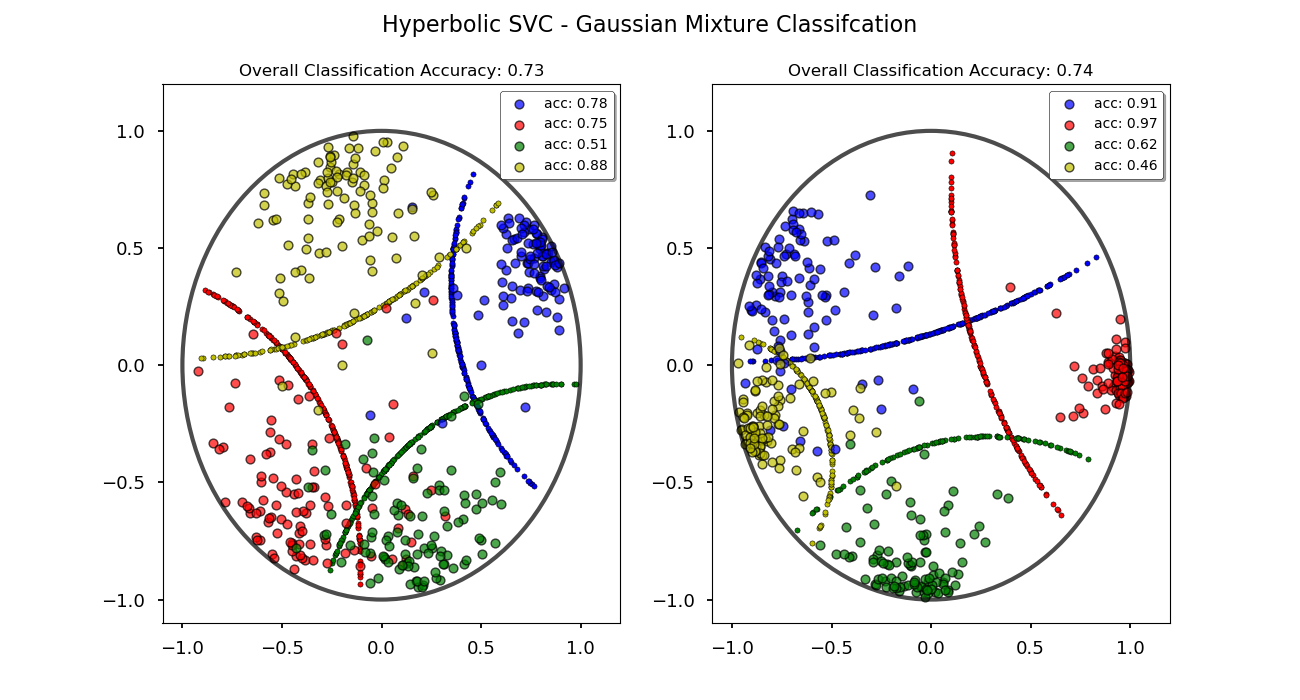

Hyperbolic Support Vector Machine - nbviewer

- Linear hyperbolic SVC based on the max-margin optimization problem in hyperbolic geometry [5].

- Uses projected gradient descent to define decision boundary and predict classifications.

-

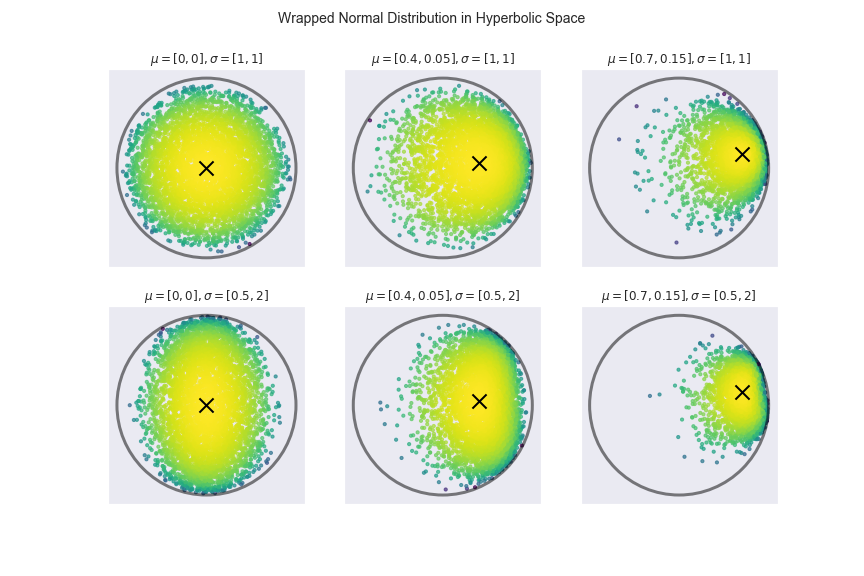

Hyperbolic Gaussian Mixture Models - nbviewer

- Iterative Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm used for clustering [6].

- Wrapped normal distribution based on using parallel transport to map to hyperboloid